|

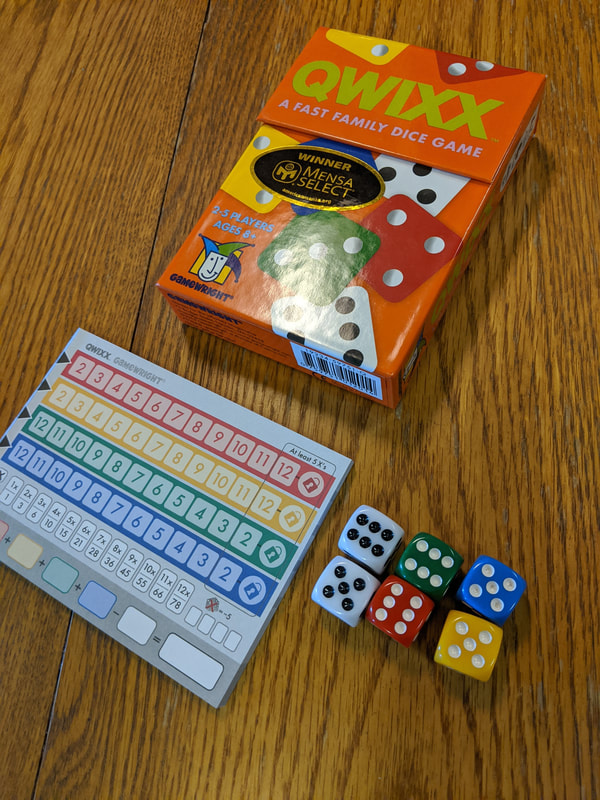

Wait, when did this become an EDUCATIONAL blog!? Blasphemy, I know, but hear me out for a moment. When spending time with my extended family, I'm often the one called upon to entertain or regale them with a new game to play that they've never heard of. Unlike my side of the family, though, this other side doesn't necessarily share the same intuitive enthusiasm for tabletop play and focus. However, my niece and father in law are both very curious, and will always try something new with fervor and flexibility, even if it isn't their norm. So each night of our socially distant "vacation", I have taught them a game. Nothing too crazy - no Power Grid or Defenders of the Realm territory; this is NOT the population to play-test my RPG-in-a-box (the last test, though awesome, ran 4 hours straight). No, I'm giving them games that are completed in 15-30 minutes tops. Games with simple rules that are easy to pick up, but challenging to master. And in playing and teaching these games, I noticed something revealing. I've played these games before, but not extensively. The rules and mechanics are few, but structuring and planning your moves takes forethought, organization...and MATH. Yeah, you heard me. Organizational, quick recall, multiplication, probability, and risk assessment. I am not a genius [though I've never been tested ;) ]. I have struggled with so many facets of my life that others excel at in common practice. And yet, I was executing key functions of my play in record time (apparently). Chunking numbers and weighing moves with precision and poise, ready to help my fellows immediately if asked, because I could SEE all of their options laid out. And to think on this more deeply, it is simply that I have had more PRACTICE utilizing these skills than they have. I've always had a good "math brain." Numbers and probability blended with mechanics and organization; this is why business and budgeting come so easily. And when I play these games with others who have also a history of tabletop gaming, I find that they, too, have obtained a general skill-set in "quick" math and organization, and I venture that this is because they practiced like I did. We practiced through play. So let me share with you three simple games that are quick on the draw and you can be certain are also helping you and your kid master some math facts (DON'T TELL THEM). Chunking and Pairing - QuixxQuixx is a game you learn in minutes. On your turn you roll six dice (2 white, then one each of Blue, Yellow, Green, and Red); then you make one or two choices based on what you rolled. You make these decisions in order. 1) You add the two White dice together, and decide to use that number or not (and other players can do this). 2) You pair ONE White die with one of the colored dice and add those together (only the active player does this). You decide to use one or both of the numbers you've "chunked" and cross them off - white is any color you want (#1), color is the color that white is paired with (#2). The thing to remember in Quixx is that each row is accessed from left to right in sequence. This means that if you cross out your Red 4, the game actually tells you to put a line through 2 and 3 on your sheet. That's because you no longer have access to them, even if you roll a "2" or "3" later. And you HAVE to cross off SOMETHING, whether it be the White, the Color Pair, OR, if neither of those are desired or possible, a Penalty Box (the game ends after four of those are crossed off). As you cross off more colors, your end score is multiplying, so more crosses in any color is a good idea. However, after you have at least FIVE crosses in a color, if you roll (or someone else rolls with White on their turn) the furthest number to the right, you can cross off THAT number and the Lock symbol next to it, and LOCK that color. This removes it from the game, and nets you two more crosses for your total. When two colors are Locked, the game ends. With that impetus, the game becomes a balance between holding out for those low or high numbers, trying to avoid penalty boxes, and trying to end the game faster by Locking two colors. Building Skills: every turn you're rolling dice, chunking quick addition, and comparing those values to desired outcomes. Us D&D folks do this all the time when we roll our favorite greatsword or fireball, so our eyes are used to putting together the numbers into easier sets to add, but the additional value comparison and choice of strategy adds a new layer to that judgement. Simple, yet complex. Anyone playing will get A LOT of practice in quick number crunching and value assignment. Probability and Risk Management - Category 5 / 6 NimmtThe game known as 6 Nimmt was a joy to play in my household growing up. Introduced to us by my eldest brother, the deceptive German game involves placing numbers in rows by the closest ascending value, filling slots in each row. If your number WOULD HAVE filled the sixth slot in a row, you must collect the five previous cards and add them to your score pile. Your "sixth" card then becomes the first in the new row. This is a game like golf. Points are bad. Each card has upon it a certain number of oxen, each worth a point. Cards have anywhere from one to seven points, and with how the game is played, some rows can add up VERY QUICKLY. But it's not all terrible. The game uses a deck of 104 cards and can be played with anywhere from 2 - 10 players. Each player starts with a hand of 10 cards each and selects in secret each round what card they'll play. After 10 rounds, everyone's hands are empty and we total up how much each of us took. This keeps rounds moving, but how many people are actually playing MATTERS in terms of probability. See, with 2 players, you deal 10 to each player, then set out 4 cards to begin each of the four rows. That's only 24 cards out of 104 that are in play. You don't draw cards during the round, so what you have is what you have. Now why does that matter? We each select a card every round and place it face down in front of us. When each of us has selected a card, we flip them at the same time. After that, the outcome to the round is mostly automated. The lowest number is placed first - it goes in ascending order within the closest distance to a number. If we use the above example, where the right-most number in each row is what we are comparing against, and with three players, we had the following numbers: 54, 16, 87. 16 is placed first, settling in right next to the 14. It is the closest row number in ascending order. After that, 54 is placed...next to the 50, but not the 60, as 60 is higher than 54. The 87...is placed next to the 60. But wait! 87 is closer to 100 than it is to 60! But the numbers must be in ascending order. 100 to 87 would be a DEscending order. Say there were more cards in those rows, and the row ending in 50 was one of them. The fifth card in the row is 50, 54 would be its sixth card - but each row can only have 5 cards, so the 50 row is collected by the player who played the 54, and their 54 starts the new row. That stack of 5 cards? Well congratulations! Add those to your score pile and get ready for the next round! But what if someone plays a card that's lower than all of the right-most numbers? Well, my dear adventurers, that person (if they go first), will have a choice. If your number is lower than everything, you choose the row you want (some are better than others), taking the lesser of two evils, and your card becomes the new row (regardless if the old row had 1 or 3 or 5 or any number cards). Pay attention, though; as the row you take may mess up another's plans in probability... The reason this game changes so dramatically with the number of players is clear when you think about probability. the game runs 10 players at max with 10 cards each (that's 100 cards), then 4 cards to get things started. That means...EVERY number from 1-104 is now in play. Now your decisions have a lot more variables to consider, many of them in the form of OTHER PEOPLE and their own strategies. With less people, you can gauge different risk with less ranges of cards in play each round. It's a fascinating, fast game, with a deep strategic backbone, and a rule set of a few sentences. Building skills: risk management, probability, judgement, counting, and chunking. Sometime in the span of 10 years ago, 6 Nimmt went out of print, but its mechanics and rights were bought and reprinted in the form of Category 5. Same game, but with hurricanes instead of bulls. *shrug* Investment, Multiplication, and Risk Management - Lost CitiesIn Lost Cities, you take the form of an archaeologist or mining explorer, seeking treasure and profit from five possible sites, and competing with only one other person.

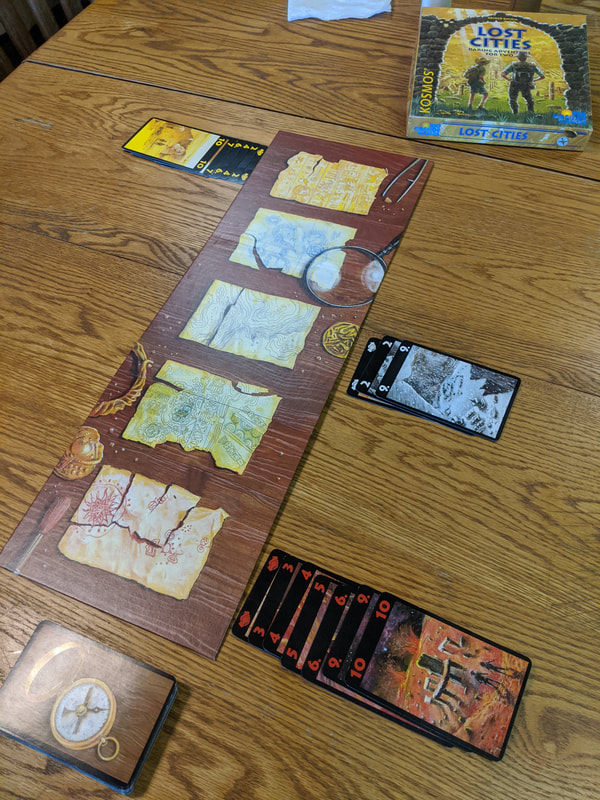

Another game involving ascending order, you place numbers in sequential order to accumulate points (profit) in the sites you want to invest in. You can't always get all the numbers you want, though, and will have to make choices carefully on when to place that 9 when you're still holding out for the 8. But I'm getting ahead of myself. On your turn, you Play A Card - investing in a dig, or "discarding" a color onto the divider that splits the board in two equal sides - then Draw A Card [either from the ever-diminishing deck OR from the top of a discard pile from the divider]. "One man's trash" and all that. INVESTING IN A DIG You invest in a dig by placing a card on your side of the divide in front of the color you desire. The number and color should match. From here, on subsequent turns, you try to place as many cards as you can in the dig to make a profit, but it ain't easy. There are two main factors in your way: 1) Ascending Sequence and 2) ...Costs. Ascending Sequence means that the numbers you place must be in ascending order. You put down a 3 one turn, then a 4 next turn, then a 6 after that (and draw a 5!)...you cannot place that 5. It's too late. Each color only has 2-10 to work with in this regard. Costs refer to the upfront cost of your dig. It comes up in end-game scoring, but you NEED to keep it in mind up front. ANY DIG you start automatically incurs a -20 point penalty. Things cost things. Tough. HOWEVER, the full range of numbers at your disposal can usually bump you over 20 points if you're paying attention. For example, I start digging in Red and over many turns put down 3-5-6-8-9-10. Add all those up and you've got 41... Subtract 20 for costs, and my score ends up being 21 for that dig. Factor in that you'll probably invest in 2 or 3 digs per game and that can add up...or 2 go really well and 1 BOMBS. But there's a third factor that can work for you or against you: PARTNERS. Represented by a little card of gentlemen shaking hands, you can have up to 3 partners (probably investors, but you get the idea) in your dig's stack, but they must be played at the beginning of the sequence. One card takes your end score (after the -20) and multiplies it by 2. 2 cards = x3. 3 cards = x4. Sounds pretty great, right? Except this can backfire. If you don't turn a profit, your partners don't either, and those multipliers count with negative points too. So I've got two partners up front, then my 21 in total from above. 21 x 3 = 63 points. Huzzah! But my other dig has three partners up front and I only managed to get a measly 3 and 9 on it. 12 - 20 = -8... x 4 = -32. All told, I'm actually back to 41, but that was an ouch, and if you're not careful with your spread, things can get real tough for you when the piper comes to collect his debts. Building Skills: My wife and I LOVE this game. There are many strategies to win and it's a great way to cultivate patience, risk management, and portfolio business. Plus, with the game ending once the deck is depleted, using that "discard" option is a leet hacker play to prolong the game so you can get that last...10...down! Happy gaming. -Adamus

0 Comments

Today we're going to revisit my youth and share with you one of the first drinks I ever learned, and continue to enjoy! I first learned about this drink while visiting a friend in Maine, and it stuck with me. However, it seems that very few people actually know about it. When I ask for it, I'm often met with a confused look. Luckily, it was burned into my memory, so every time I might order it I get to teach someone a new drink. Also, in my responsible social gatherings, this was the drink of request for many of my friends; they knew I could mix it and it was downright delicious. Sex With An Alligator / The Alligator TailOrdering this is often hilarious. It usually comes out as "Could I have a Sex With An Alligator?" The waitress would nod, walk away...then return after about five minutes and ask, "You want the drink, right?" ...I didn't realize the alternative was an option?

The "Alligator" is a layered drink. You are to pour each element in order, so as to build a certain aesthetic as well as the progression of flavors. The Recipe I Learned 1. Midori (melon liqueur) - usually 2 oz 2. Pineapple Juice - 2 oz 3. Raspberry Liqueur (Razzmatazz or Chambord will work great) - 2 oz 4. Thin layer of Jagermeister - about 1/2 oz or less, depending on preference, floats on top The visual effect...is a murky swamp. Like the home of our favorite big scaly body of teeth. This is a shooter, approximately 3-4 shots total. A little licorice at the front, then nothing but candy. It sneaks up on you, though. Make sure to respect the big green. Want a little more orange in your drink? Then you want my Crocodile variation. Just switch out the Pineapple juice for Orange juice instead. Other versions cite using Whiskey Sour mix, but that wasn't the tasty version I learned. You want it? Switch out the Pineapple juice for a Sweet and Sour mix, or the Whiskey Sour. Go figure. Shoot Responsibly. -Adamus A while ago, Adamus released a blog post detailing ten questions that he asks his players in order to create dynamic stories and engaging characters. Recently, I did a similar practice, and asked ten of my own questions as part of a session zero for my latest story-based campaign. This is due to some profound discoveries I’ve made about myself and my relationship with Dungeons and Dragons, including that I’m energized by story developments over combat, and that my focus on mechanics has been motivated by story reasons, not quantitative ones. I want to tell my character’s story, not have it told to me by the Dungeon Master.

The centerpiece of all my favorite stories is the characters. A hackneyed plot can be saved by unique and deep character development, while often the opposite can’t be true. I tend to reject stories that have deep world building that lack great characters. So what makes a great character? Personally, I find my favorite characters to have the following traits: 1) Great characters have some kind of conflict, whether it’s the conflict of their view versus reality, or a conflict between what they preach versus how they act. However this conflict manifests, it’s something that hangs over their head. 2). Great characters learn as they go. They aren’t the same person at the end of their story as they were at the beginning. I find characters that repeat the same mistakes over and over again to be frustrating, especially if the lesson they learn is the same one. That doesn’t mean their character has to do a 180 every time they fail, but there should be some kind of change, even if it’s gradual. 3). Great characters have a goal, even if it changes as it goes. Sometimes I’ll hear, “My character doesn’t have a goal. They’re just in it for the coin.” THAT’S A GOAL! They do stuff because they want stuff. And just because they start a journey where they’re in it for the money doesn’t mean they don’t create attachments and relationships as the story progresses. In fact, that may create a conflict that they learn from, changing their goal as they go. It can be a cycle. Obviously this is a gross reduction of the complexity we could discuss when it comes to great characterization, but the last point I’d like to make is that none of these traits have to be big in scope. Some of my favorite stories are more intimate, personal journeys than they are grand quests that span the globe. Aang’s quest (from Avatar: The Last Airbender, now on Netflix and you should totally watch it) to convey his feelings to Katara is just as if not more important to him than defeating Fire Lord Ozai and saving the world from the Fire Nation military. Another great example is the Mandalorian, where the titular character’s quest of protecting Baby Yoda (don’t care what his canon name is) tends to be more praised than the entirety of The Rise of Skywalker. The rise of stakes does not mean the rise of investment, and often it’s the little changes that make the biggest difference. So with that in mind, the ten questions I asked my players were intended to ignite their creative energy and deepen their understanding of the characters they wanted to portray. I started by asking my players these questions sequentially, gave them some time to let them simmer, and then worked through each question with the players in one-on-one follow up conversations. That way, they wouldn’t feel silly in front of other people. It was just them and me. Here are the ten (and some of them have multiple parts): 1). Where were you born, and who was your family? Are any of them still alive? 2). Did you grow up in poverty, nobility, or the middle class? 3). How did you come upon your current profession (character class)? Who trained you? 4). Who else helped or hindered you along the way? 5). What’s your character’s view on politics and religion? (Ambivalence is a perfectly fine answer) 6). What is your character’s current goal(s)? 7). What does your character regret? 8). What lie does your character tell themselves to make things easier? 9). How does your character see their story ending? 10). How is your character acquainted with the party, or what about the mission hooked them in? Now the first six are standard fare session zero questions. There are plenty of content creators that have spoken eloquently to the value of considering those factors when designing a character and their story, especially if you want to prepare your players to be situated in the world. Question 1 allows the DM to give you extra information on your home town or region that you as a player can leverage in-game by calling out specific details that heighten the table’s immersion. Questions 2 and 5 may heavily impact your outlook on the world and social dynamics. Question 3 grounds your character’s abilities in the world. The second half of Question 1, the second half of Question 3, and all of Question 4 help create NPCs that the DM can use as informants, allies, and even possibly rivals for your character. And, Question 6 gives your character a motive and direction to create their own objectives if they so choose. You’d be surprised how many players have trouble with Question 6. Until they get into gameplay, goals may feel abstract or silly. After all, the DM gives the party their initial mission that then helps the players leverage into proactive goals, right? Questions 7 and 8 are the ones I noticed give my players pause. At Session Zero, nothing about them seemed too out of the ordinary, but in one-on-one conversations, every single one of my players had to take extra time to answer them. They’re hard questions we as a culture don’t have enough practice in exploring in an articulate way, and by making Dungeons and Dragons a safe space where you get to make an entirely new person to explore these questions, it can give us judgment-free practice to ask these questions of ourselves. Now to pause for a second, let me make this clear: D&D is not therapy. It can feel therapeutic, but it is not a substitute for therapy. Your friends are not therapists, and even if they are, a recreational game is not the place for dealing with very real issues of mental health and wellness. What I’m saying here is that tabletop role-playing can be a launch pad for personal growth and development, but I will repeat: This is not therapy. Therapy is therapy. D&D is D&D. Both are valuable, both have their place, and there are many professionals much smarter and much more equipped than me that can speak to D&D’s relationship to therapy as a supplement, not a substitute. With that out of the way, we have another interesting thought experiment with Question 9. How does your character see their story ending? This can be an easy one to dismiss by saying “They don’t think about that”, but if forced to come up with an answer, what would you say? It’s another hard question, but again allows for a safe space exercise to really map out your character’s arc. And just like any of these questions, the answer can change over time. And then Question 10…is just more standard stuff. Build an adventurer, someone who can at least have a coworker relationship with the party if not an invested friendship. Really, the meat and potatoes of these questions are 7, 8, and 9, and how they can inform the answers for earlier questions. I can’t tell you the number of times having conversations that a player would give me a regret and I would reply “Does that inform your goal?” or “That sounds like someone that hindered you along the way”. These questions aren’t disconnected from each other. Now just to give an example of how these questions fit together, let’s go back to talk about our Last Airbender, Aang, and how we might answer these questions for him: 1). Aang comes from the Southern Air Temple, and his family is unknown. 2). Aang grew up with the Air Nomads, meaning he lives outside of the economic hierarchy of most communities. Technically, this also means he’s impoverished. 3). Aang was trained by Monk Gyatso, who taught him everything he knows about Airbending (abilities of which would be reflected in his character class). Later, he learns to communicate with his past life, Avatar Roku, in order to learn what it means to be the Avatar (again, reflected in his character class). 4). Aang is helped by the waterbender that discovered him, Katara, and her brother Sokka. He is often hindered by his rival, the Firebending Prince Zuko (we’re talking just season 1, so no spoilers). 5). Aang is technically the center of a loose religion dedicated to the Avatar, of which he’s a Messiah figure tasked to rebalance the world. He detests the War, and has vowed to defeat Fire Lord Ozai to end it. 6). Aang’s current goal (season 1) is to travel to the North Pole and learn waterbending, after which he’ll learn earth and fire so he’ll be properly trained when taking on Ozai. 7). Aang regrets leaving the Southern Air Temple, believing he could’ve helped fight off the Fire Nation invaders if he had stayed behind. 8). One of the reasons Aang is such a dynamic character is because of how he lies to himself. One of the best lies is “I’m just a simple monk” before entertaining a flock of young girls. 9). Aang isn’t sure how his story will end, but as he progresses through Season 1, he can at least see the end of his current arc: becoming a master waterbender. 10). Aang joined the party when Katara discovered him in the iceberg. Now to drive this point home further, Avatar was awarded the Peabody award for excellent character development. Part of this is that Aang’s rival, Prince Zuko, can answer these questions as well (if not better) than the protagonist himself. 1). Fire Prince Zuko is the son of Fire Lord Ozai of the Fire Nation. 2). He was born into nobility and is accustomed to underlings following his orders. 3). He’s still being taught firebending and philosophy by his Uncle Iroh, who is his greatest ally on the hunt for the Avatar. 4). His father permanently scarred his face after publically forcing him into a duel after “dishonoring” him, and his current efforts are often hindered by the interference of the Fire Nation’s Commander Zhao. 5). Zuko believes the Fire Nation will win the war, and although he believes the Avatar is still alive, he rejects any worship of him. 6). Zuko’s current goal is to defeat the Avatar and regain his lost honor following the duel with his father, Fire Lord Ozai. 7). Zuko regrets having spoken up at a war meeting, where he criticized the heartless tactics of a high ranking Fire Lord officer. His father interpreted this as dishonoring his family, and the Fire Lord punished him in a highly publicized duel where Zuko was scarred. 8). The lie Zuko tells himself is that if he defeats the Avatar, his father will finally love him. 9). Zuko sees his story ending by defeating Aang in combat and returning home with honor, where he’ll inherit the throne of the Fire Lord. 10). Zuko met the party after seeing a column of light caused by Aang’s reawakening from the Iceberg. Now you tell me. Which character sounds more compelling? I’ve done this exercise myself with the character’s I’m currently playing, and it’s revealed a lot about them and my preferences in character creation. Maybe you’ll learn something about yourself too as you answer them for your characters. I’m excited to hear your thoughts about this. If you found this blog through Facebook, make sure to comment below or shoot us an email at [email protected]. Study Hard, Play Hard, -John Next on our simple "classics" is the Manhattan. Clearly a vehicle for Rye whiskey, the Manhattan is a staple in any bartender's repertoire. It's simple, clean, and a deep amber. Another "gentleman" drink. The Classic Manhattan 1 oz Rye Whiskey 1/2 oz Sweet Vermouth 3 dashes Aromatic Bitters Garnish with a cherry Masa's ManhattanSo, how can I screw this up?

Most variations on this classic mess with the basic components. Substitute Bourbon instead of Rye, and you have something new. Use Chocolate Bitters for some weird new brew. I want something that honors the "spirit" of the Manhattan, but changes it around so some schmuck like me can enjoy it like a Real Man. So. Let's make a syrup. Nothing too complicated. Just something to add a little spice and sugar to this lovely thing. I propose the following preparation: The Royal "Syrup" 1 oz Fireball (Cinnamon Whiskey) 1/2 oz Drambuie 1 tsp brown sugar 1-1.5 oz Dr. McGillicuddy's Cherry Liqueur Stir that up. Masa's Manhattan 1.5 oz Jack Honey (Tennessee Whiskey) 1/2 oz Sweet Vermouth 5 dashes Aromatic Bitters Pour Masa into a high ball glass with ice, then pour the Royal over that. Sit back by the fire and sip away as you watch the dragonkin gamble across the way. Not smooth enough for ya? Then do the blasphemous thing and pour some Coca-Cola to fill the glass. You won't be disappointed. Sip responsibly, travelers. -Adamus The following words are a reflection on the strange progression from last November (when the community center I once DM'ed professionally for closed) until now. More lessons, better observations, and a stronger step forward. Come along into my head and heart. Death and RebirthWhen you're running a business, certain theologies creep in. You're constantly weighing cost and benefit, risk and reward, with every new endeavor. Often, you take risk - to stretch your creative muscles, to seek new tiers, and to press your luck for that big win. Sometimes that works, often it doesn't. And when you're running games professionally as one facet of a much larger business, the pressure to perform just to stay afloat can create subconscious perspective and habit, some of which are more detrimental than affirming. To be frank, putting pressure on myself to put "butts in seats" in order to simply run a game...destroyed me. I was constantly pressuring myself to strike a balance between margin and equity. The quantity of players mingling with the quality of the experience. Now, I went along with this idea, because, let's be honest, Game On! (my section of the larger business) knew what it was doing, and it was doing pretty well for the small tribe it had fostered. If it were ONLY that, perhaps the total might have survived. But it wasn't, and the added pressure to carry the weight of everything else going on forces you to consider adding one more player when 5 was plenty, because one more player allows the class to cover its overhead, and actually make a sliver of profit for once; one more player keeps the lights on a little longer, the heat running. And some players clash. Some tables work with a certain group of 4, but that 5th player throws it all out of whack, while other tables struggle with 5 only to synergize with 6. Some can grow and get over it, and others just can't. But these people are customers, so I would weigh the business's success to form a Social Contract, and hold players to it. This helped some groups tighten up; achieve a greater synergy, and augment play to new heights. Others, it drove the nail into the coffin. Players stopped showing up (which means they weren't paying), or would "forget" to pay. Do that enough, and now it costs too much to even run the game and the campaign gets scrapped. When a single player at a table is the difference between your business succeeding or failing, it can CHANGE the way you view your game mastering. You tend to sacrifice more of yourself to make the clients "happy" or satisfied; you bend over backwards to make it work with way more players than the table should have; and you put up with things that legitimately bother you because the alternative is that client quitting. It wasn't like this all the time, and as we went along, I became more acclimated to the idea of "owning" my tables. We set boundaries, we stopped and hashed things out, we posted clear and precise expectations for our tables. We adapted, and made our experiences tighter and more immersive with every new lesson. I am a thousand-times grateful for the professionalism I gained by treating this pursuit as my full-time job. And. When the business as a whole shuttered its doors and I had 5 campaigns unfinished without a space to play...we adapted. The most splendid tribe of people in history rolled with the changes and followed just me instead. I did my best to honor the rapport I had cultivated over the last three years and kept the transition as seamless as possible. So, games once in a community center are run in a dojo, or a home, or a rented game store. Wherever we can gather, we play. And THEN. A pandemic. We moved every campaign to online play only, and kept rolling as I learned the ropes. And, just recently, I finished one of those massive campaigns (Knight Owls Season 3 just ended this evening - it was AMAZING). As humans approach the close of something, they often become much more reflective on the whole experience. At the end of June, I was BURNT OUT. Creatively spent, frustrated, emotionally exhausted; I needed time to reacclimate to my stories, and find the fire again. I did. And. I thought deeply about the future. I thought about Knight Owls Season 4 here and there, toying with curious scenarios. I thought about Pugmire, and Exalted, and my old 4th Edition Knights Of The Round campaign from college. But most of all, I thought about Gray Owls; where it was headed, where I lost my players, where I lost myself, and my excitement when I considered the NEXT campaign. All the things I would fix for NEXT TIME; lessons learned once more. Lesson 1 - It Took Loss To Free MeTo be blunt: Questers' Way needed to close in order for me to flourish. It took the loss of that job to allow the space to restructure EVERYTHING on MY terms. Finally. To not worry about overhead, and mark down some of the best experiences I've been able to run at a table, digital or otherwise. All that professional training to justify a price tag still pays off, but play to play and player to player, how that price resolves...has no pressure on the electric bill. This means I can adapt to the needs of others based on what I'M comfortable with...because I'm the boss. Lesson 2 - This Is MY TableAnd I will run it well. However, just as some players don't always fit together, some GMs and their style don't jive with certain players. I'm pretty easy-going, but over the years I've established some strict boundaries. These help with having clear expectations at the table, meeting my players as fellow human beings, being patient and kind, and allowing everyone (including myself) a bad day. And the best thing? My brand is my own. It won't be bigger than me. So I expect my players to talk to me if something's up. In fact, they kind of have to, there's no one else. Meaning I'm not out of the loop on the stuff that matters. In order to run an effective table, I need to know what's going on. When I was working in a larger organization, it was a weekly occurrence that I would be "out of the loop" on something that affected me and my campaigns directly; the communication infrastructure was terrible sometimes - there were just too many heads to the hydra and it never got back to the heart. Not anymore. Looking Forward |

Adam SummererProfessional Game Master musician, music teacher, game designer, amateur bartender, and aspiring fiction author. Honestly, I write what I want when I want. Often monster lore, sometimes miniature showcases, and the occasional movie/show review.

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed